Even if I don’t consider myself the kind of person who would consider contemplating mountain-climbing, my brain frequently preoccupies itself with thoughts of actually doing it. I seem to have invasive dreams of losing a grip on my rope and tumbling down the mountain: “Fool! You’re a total fool! You climbed all the way there just to plummet back down!”

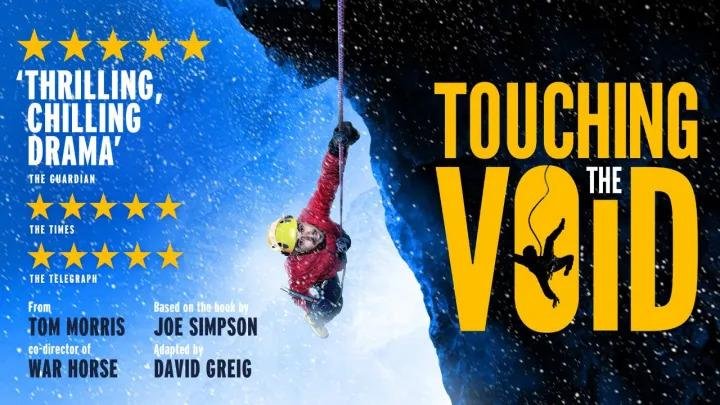

There is a more daunting movie than the deep, dark holes of my imagination. “Touching the Void” is the single most harrowing movie that I can think of related to mountain climbing, even with all the other movies out there. I have read some reviews of the film and some of the critics didn’t seem too shaken by it (my friend Dave Kehr certainly kept his composure) and absolutely have no clue why their nightmares are not mine.

While watching the film, I didn’t feel the need to make any notes. I was completely captivated and held in such awe that it was stunning. Instead of contemplating the “pseudo-documentary format” of the film or how the camera captured Simpson’s fall into the crevice, “Touching the Void full movie watch here fmovies was more horrifying for me than any other horror film could ever be.”

This movie highlights Siula Grande’s attempt by two young British climbers, Joe Simpson and Simon Yates. The climbers were ‘in a good training shape,’ and ‘bold’ enough to try what is called a one push method of climbing, which is a form of climbing where all equipment is carried rather than having established sections of stored gear throughout the route. The duo limited their supplies and aimed ‘to go up and down quickly.’

However, they were faced with a set of problems. A near-blind snowstorm and strong winds were a constant problem for them. As they started their planned descent, the various obstacles such as crevices and the concealed peril of hidden falls threw them off course. They executed strategies like having one person rope tied and braced at different points to hold the rope together; this way, when the other fell, it wouldn’t affect the entire structure. Unfortunately, a fall caused Simpson to break his leg by having the calf bone rammed right through the knee's socket. He was aware the extent of the injury meant instant death due to his condition. Simpson recalls being surprised to find Yates opted to attempt getting him out after deciding, the duo clearly left without possibility of rescue.

Simpson's survival is portrayed in The TV movie where Simpson and Yates are shown in real life, dressed in classic attires set against featureless backgrounds, looking into the camera, reflecting on their journey in their own narration. We also observe the ordeal being performed by two actors (Brendan Mackey as Simpson, Nicholas Aaron as Yates) and experienced climbers serve as stunt doubles. The shooting locations included Peru and the Alps, with the climbing scenes being completely realistic. The performative distractions of those scenes are unrecognized due to the heavy frostbite, snow caked faces that make them barely recognizable.

Yates and Simpson had a rope measuring 300 feet. Yates' strategy was to lower Simpson down 300 feet and wait for a pull on the rope. That meant Simpson had settled in and it was safe for Yates to descend and repeat the process. A reasonable strategy, until, after dark in a blizzard, Yates lowered Simpson over a cliff and left him suspended over a chasm of unfathomable depth. Given that they were out of earshot during the blizzard, the only information Yates had was that the rope was tight and stationary which meant he had to be slowly losing his footing, or at least the precarious ledges he had created to keep himself stabilized. After roughly an hour, it dawned on him that Yates was, in fact, hanging mid-air and Simpson's remaining tether would result in an inescapable scenario for both. So, his only option was to sever the rope.

Under those circumstances, we've all agreed that Yates made an instantaneous decision, but what follows is difficult, almost incomprehensible to process, and this is the chain of events that transforms the movie into an astounding tale of survival.

If you're planning on seeing the film, which I highly recommend, you might want to hold off reading the rest of the review until later.

Incredible as it may seem, Simpson falls into a crevice, but is prevented from completing the plunge by several snow bridges that he crashes through and comes to rest on an ice ledge which has a drop on either side. Here he is, in utter darkness and frigid cold, with no means of igloo fuel to melt snow, no food, and a dying lamp battery. To make matters worse, he is ravenous, dehydrated, and his leg is slowly but surely inflicting excruciating pain due to the bony teeth that are grinding together in it (a pair of aspirins didn't help much).

It is obvious that Simpson cannot make the climb back up out of the crevice, so ultimately he has no choice but to stake everything on a plan that appears to be madness but was his sole alternative to dying while waiting for death: He goes and decides to take the risk of using the rope to lower himself into the unknown depths. Only if he’s certain that the distance exceeds 300 feet, if not, then truly, he will have reached the end of his rope.

A floor exists far beneath the mountains. In the morning, he remarkably sees light and can, astonishingly, crawl to the mountainside. This is only the first part of his journey. Somehow, he must find a way to descend the mountain and traverse a plain filled with numerous rocks and massive boulders which makes it impossible for him to walk, forcing him to attempt to hop or crawl despite the pain he feels in his leg. Clearly, he was able to achieve this, considering that he is alive today to author a book and star in a documentary film. How he managed to achieve that is quite painful, and at times had me covering my eyess from his suffering.

The film, directed by Kevin Macdonald, is a stunning masterpiece. Macdonald also directed the Oscar-winning film “One Day In September” about the Olympics in 1972. This film captivates with its storytelling brutal directness and simplicity. Kevin does not attempt to create additional suspense or drama because it isn’t needed. Rather, the viewer witnesses the story in disbelief as it is told to them.

Eventually, we discover that Simpson's leg was fixed after two years of surgery (and, as you may have expected, he returned to climbing). At this point, I was thinking of Boss Getty's line about Citizen Kane: "He's going to need more than one lesson." I can only pray that the remainder of the speech does not also pertain to Simpson: "… and he's going to get more than one lesson."